Articulate the Evidence of Value | Chapter 1

By Ralph Morales III  5 min read

5 min read

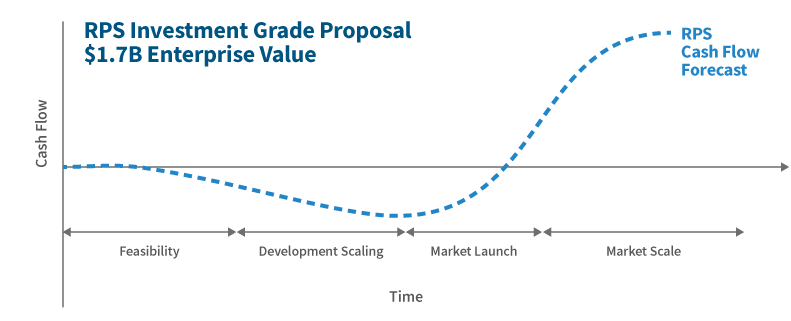

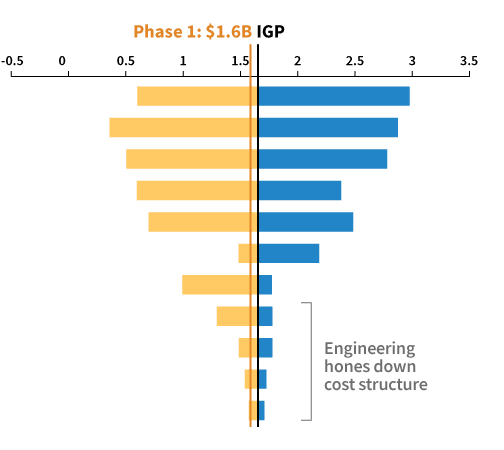

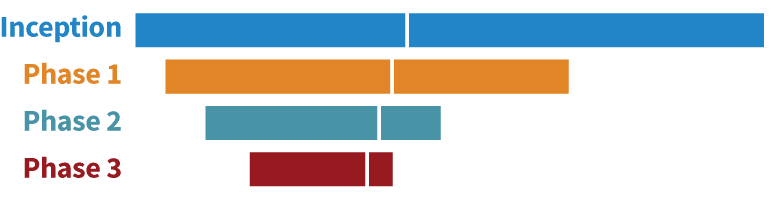

Based on these favorable factors, we created an investment grade proposal for the new on-demand photo printing business. The projected size of the market led us to project a cashflow that valued the enterprise at $1.7 billion. We would invest in feasibility demonstration, development and production scaling, and market launch, and then earn back our investment and profit in market scaling.

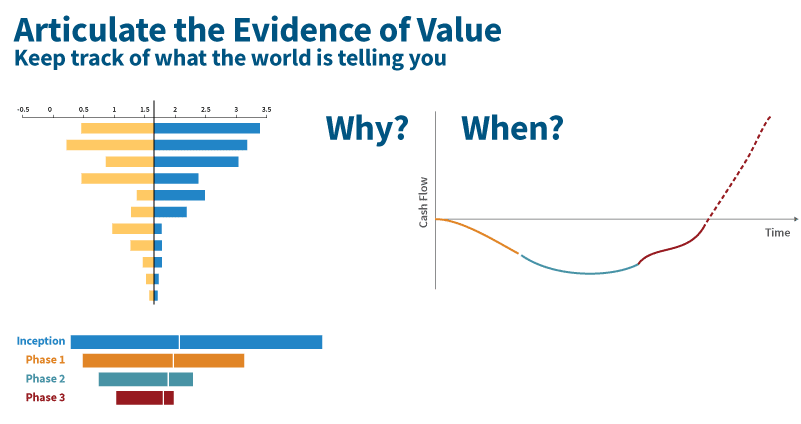

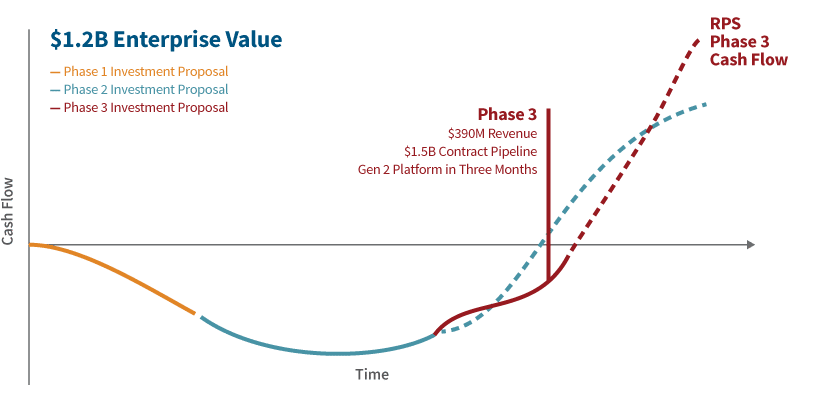

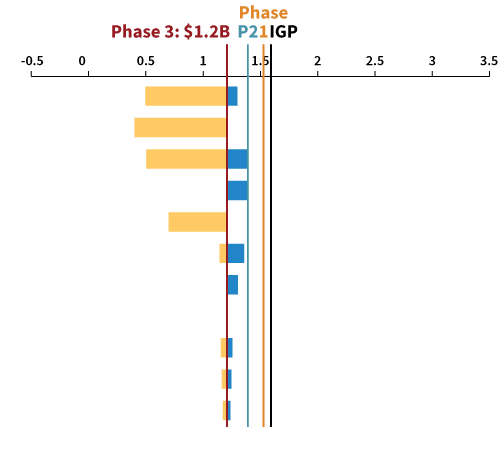

As the project progressed, we met our objectives in feasibility demonstration. It took a bit longer than we expected and cost a bit more, but our cashflow projections still forecasted a $1.6 billion valuation. Development and production scaling and market launch took substantially longer than we’d planned, but we were still on track to a $1.4 billion valuation. We had initial market acceptance, nearly $400 million in revenue, and a contract pipeline of $1.5 billion. There was more schedule stretch during our market scaling, pushing our valuation down to $1.2 billion.

This reflected the knowledge we gained over the course of the three phases. On the plus side, we were far less ignorant of the product-market fit. On the minus side, the fit was not nearly what we had hoped. The probability was that the future would keep pushing the value of the business ever lower, erasing the projected valuation. At each phase, the business unit had focused on action plans to “drive results” along each dimension without a review of the investment thesis.

We were gathering market feedback through our operations and while all of it went toward annual planning goals, little of it went toward a review of the evidence of value.

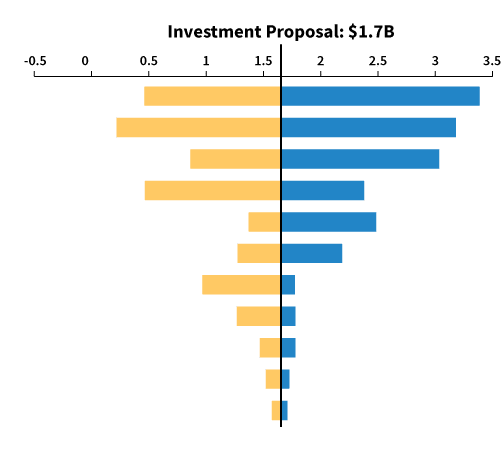

These bars represent the total range of possible program value at each phase, with the white line showing the most likely value for that phase. With each phase, the total uncertainty (the length of the bar) shrank, but the balance between upside and downside progressively shifted in the downside direction. Have you ever witnessed a program doggedly (heroically?) trying to survive against market forces?