The strategic choice canvas is yet again another great post from Ricardo dos Santos. Ricardo was a thought leader in my session on ‘Failing Forward’ at the IIR’s Back End of Innovation 2013 conference. We at SmartOrg have used for decades similar canvas format in strategy and innovation, called a strategy table. Here is a best practice guide showing how it can be used for innovation.

And now, on to Ricardo’s blog:

The Strategic Choice Canvas

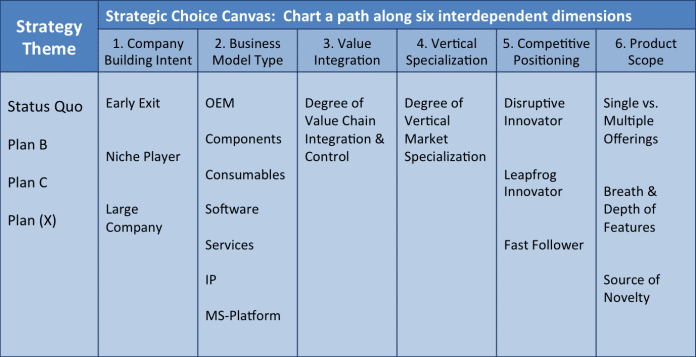

Based on your assessment of the current situation facing your startup or innovation, the Gut Check (including a good grasp of the past and changing conditions ahead), it is time to put your core idea and inertia through the strategy ringer, or a set of decision-making criteria that should improve your prospects for maximizing or over-indexing the value that you can create (based on what you know now and believe to be true).

No strategic planning framework can claim to be perfectly comprehensive, but I believe the following six sets of interdependent choices should provide sufficient guidance for a new venture’s strategy, covering both the theoretical and practical aspects of strategy I’ve been conferring to this point.

The six interdependent strategic choices are:

- Company Building Intention.

- Business Model Type.

- Value Integration & Control.

- Vertical Market Specialization.

- Competitive Positioning, &

- Product Scope.

1. Company Building Intention:

- Early Exit

- Niche Player

- Large Company

An Early Exit strategy usually implies a sale to an incumbent before that incumbent thinks it is wiser to build vs. buy. This is a risky strategy if the startup does not build any capability to commercialize and simply showcases attractive technology to be acquired, but it can be an effective strategy in several circumstances, and especially in certain industries with extremely long product lifecycles, such as biotech. If you follow this strategy, you have to favor business development efforts, early and often with strategic investors (with the goal of lining up at least one major buy-out agreement).

A Niche Player is usually the least risky strategy if the goal is simply survival, as it implies a more conservative capital raise, a trade-off for the bigger upside of being the market leader in a large market. For a technology company, the niche strategy can include the ‘R&D licenser’ or project contractor variant, where the founders realize that they are best at inventing than commercializing, and thus prefer to stay small, leveraging the infrastructure of others to diffuse their innovations, while they move on to the next discovery.

A Large Company strategy is also risky in that it usually implies a longer time to the mainstream market, high capital requirements (peak-funding), and the ownership dilution and loss of control dilemma – Certainly it’s the strategy to follow if ‘go big or go home’ prevails as key to the vision and values of founders and investors.

It is important to understand your intention so as to prioritize the associated exercises necessary for achieving strategic congruency (e.g. corporate partnerships, pass-through license agreements with Universities, relations with VC’s, etc.). This doesn’t mean to say that you can’t change your company building intention as you progress – Qualcomm, my ex-employer, started out as a niche-player with founders explicitly not wanting to build a large company (and chiefly allergic to VC’s), but when the CDMA opportunity for cellphones arose, well, plans changed (sans VC’s).

2. Business Model Type:

- Original Equipment Manufacturer

- Components

- Consumables

- Software

- Services

- Intellectual Property

- Multi-Sided-Platform

- Hybrid

An Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) business model is the quintessential way to provide value directly to an end customer (B2C or B2B). I’m mostly talking about hardware goods, where traditional product development & marketing, systems integration and supply chain management are the requirements to play. If you’re not good at either of those things (or hate the added uncertainty), you may want to consider the component business model instead. Sometimes you have no choice but to start off in this category as a vertically integrated player, if you’re inventing an entirely new product category and then move to a select horizontal position as the market matures – this is how the Qualcomm story unfolded (first it made phones and cell-tower infrastructure to drive CDMA adoption before settling on its components + IP strategy).

A Components business model is the way to provide value-inside to someone else dealing directly with the end customer (thus B2B). You can compete on cost or technology leadership and it isn’t always clear how much attention you must pay to the end user vs. your B2B customers. (You’ll occasionally hear advertisements from players in this model, e.g. BASF “We don’t make a lot of the products you buy, we make them better”). Industry maturity and structure is vital to selecting this strategy – You want the right amount of customer concentration and lots of capable suppliers. You’re mostly hedging that this is a wiser choice vs. risking direct competition with deeply entrenched OEMs. A vertical integration into reference designs, API’s, etc. is an alternative way to get closer to the end-user, while not competing with your B2B customers.

A Consumables business model is the gift that keeps on giving, if you’re able to earn the loyalty of your customers (B2C or B2B). You can compete on innovation and or high-switching costs. This model is often coupled with an OEM platform, on top of which the consumables get consumed (yep, the famed razor, razor-blades model). Depending on the industry, the underlying platform can also be opened to partners’ consumables (see MSP’s below). Not all consumables are alike – the highly differentiated earn a much higher premium, but in return, the platform may become a loss leader. Most life-science-tool firms such as the Next Gen Sequencing OEM leaders Illumina & LifeTech operate a complementary consumables model in their core research markets and have recently forayed into higher-margin clinical consumables, namely diagnostic assays.

A Software business model is the ultimate scaling machine (B2C or B2B). This is quite a broad and fast moving space and thus hard to generalize a description. Certainly you’re looking for scalability in both the product and distribution, taking advantage of the cloud as much as the next guy, with security and performance as some of the tradeoffs. The B2B software space seems to be back in vogue, but with the proliferation of consumer devices, this should remain an attractive B2C space. There is a marked difference in software businesses that are heavy IP dependent (software is the embodiment of clever algorithms) vs. those that are platforms and those that are automation time-savers. For programmers (and it’s becoming easier to program), starting a business has become ‘free’ – so don’t expect this category to subside anytime soon.

A Services business model is the ultimate non-scalable machine (B2C or B2B). Of course I’m being facetious – but not really – services businesses depend primarily on committed, skilled people and those are usually hard to find (for the right price). It is also non-trivial to export a services business to another geography – So something to ponder if you’re planning world domination through a services business model. In some industries, the advantage of a services model is that it can get off with relative little time and money and it can likewise be used as a testing ground for other more scalable models. In the oncology diagnostic business that I operate in today, a services business is not governed by the FDA, and thus the preferred route of many innovators such as Myriad, Genomic Health, and Foundation Medicine – this may change!

An Intellectual Property business model is usually combined with a more orthodox approach to making money from products and or services, but it can be executed as a stand-alone choice. Intellectual Property dependent industries include high-tech, biotech, but also music and other arts. The monetization schemes for IP include licenses and royalty streams – or winning court settlements, in case of the repugnant patent ogres. An IP model may have to include an investment in continued R&D, not simply a team to negotiate licenses. This is the model ARM and Qualcomm have followed successfully, providing licenses for everyone at a fair price while continuing to invest in R&D (that makes the make vs. license decision a no-brainer for its customers).

A Multi-Sided-Platform (MSP) business model is probably the most exotic model to follow, requiring a high-degree of complexity to balance the needs of end users from those of customers and strategic partners, which are by definition, different stakeholders. The typical example of this model is the advertising-driven internet platforms such as Google, Facebook and Twitter, but it also includes e-commerce sites such as Amazon, Ebay, and Rakuten, video-gaming consoles such as Sony’s PSP and MS’s Xbox, payment enablers such as PayPal and Square, and Operating Systems such as iOS, Android and Windows. The key to a successful MSP is to provide tangible value and a common language to all stakeholders, for example by reducing search, transaction, startup, and/or marketing and operational costs.

A Hybrid business model combines elements of the generic choices described above. It is very common to see hybrid models in established tech and industrial businesses such as IBM, Apple, Microsoft, Google, Qualcomm, Amazon, GE, Siemens, etc. and also in other industries such as healthcare. Some industries, including consumer packaged goods and automotive, are just starting to adapt hybrid business models combining products and services. As a startup, it is certainly a more difficult choice to adapt a hybrid business model vs. choosing a more simplified path, at least initially as a go-to-market strategy. The theory would certainly advise against simultaneously introducing a new product and service. However, a complementary model could rapidly follow, e.g. launching an Idea Management System corporate software, followed by innovation professional services.

The description of the various business model types isn’t meant to contrast one vs. the other to say which is better in general (although there are those among the investment community that hold strong preferences). The choice of generic business model type (aka. how you plan to make money) has to be tailored to each given startup’s circumstances as well as execution preferences. Depending on the opportunity, one may or may not have the luxury (or burden) of choice. What’s important to stress is that the business model choice is certainly critical to prioritizing the research activities, hirings, and other investments that the startup will undertake. It is also a moving target – certainly searching for the right, scalable business model is par for the course at first – lest a hasty decision result in irreversible waste.

3. Value Integration & Control

The degree of Value Integration & Control certainly overlaps with your choice of generic business model, but it professes something different: This is less about the primary way to make money as it is about choosing which segments of the value or network chain are critical to tightly integrate, own and or control by other means (to maintain quality, supply, and margin, but most of all, the customer experience and innovation-edge over the product or service being sold).

This practice was best exemplified by almost everything Steve Jobs did (who was the hands-down master of this topic) “I’ve always wanted to own and control the primary technology in everything we do” SJ – that certainly included software (directly), and later, content distribution (through clever negotiating), not simply the beautiful hardware we more easily associate with Apple.

A desire for greater integration and control does of course entail hiring people with different skill sets, purchasing or leasing additional assets, etc. – so a tough tradeoff when getting off the ground. View strategic partnerships as a possible remedy, keeping in mind who will own the relationship with the customer. Certainly consider outsourcing of some or all of the things you have to make (unless you can’t keep control or inadvertently creating a competitor) – a rule of thumb followed by Japanese auto-companies may help “Don’t outsource for lack of knowledge, only for lack of capacity”.

4. Vertical Market Specialization

The degree of Vertical Market Specialization is a tough choice faced only too-often by tech-driven companies and those offering any sort of platform. This choice, more than any other, ultimately determines who your end users and customers really are. The ultimate answer may dictate branching out across various verticals to maximize growth, but at first, this is difficult to execute – at least as an initial go-to-market strategy, tackling a single-vertical (customer segment) is the standard advice – This makes sense if we ultimately believe in the concept of a product-market fit and a scalable growth engine to match – the specifics are hard to design if they must meet the requirements of multiple verticals from the start.

In the largest vs. first-to-market vertical tradeoff, most startups choose first-to-market, before ‘crossing the chasm’ to the mainstream. I didn’t label this choice as Vertical Industry as that’s over simplistic – best to dissect markets by Jobs-to-be-Done and other methods that get to the reasons people buy stuff vs. industry SIC codes. But industry verticals can still be helpful in narrowing down your search, especially in the B2B space.

5. Competitive Positioning:

- Disruptive Innovator

- Leapfrog Innovator

- Fast Follower

The Disruptive Innovator positioning is primarily designed to fight non-consumption (if something is valuable, it’s worth democratizing). It is the standard advice for new entrants – “Stay away from the incumbents best customers” (because they will counter your ‘sustaining innovation’ move with an arms-race move of their own (with a vengeance). A Disruptive strategy caters to over-served customers of incumbents or creates entirely new markets (new value systems, attributes or channels emphasized in a given product or service category) – the strategy is intended to fly under the radar of incumbents (it has to be unexpected, or it isn’t disruptive, btw). In cancer diagnostics, one can be disruptive by placing a testing platform nearer the patient (eliminating the FedEx’ing of patient blood to highly-paid specialists) or inventing a novel test (that disrupts more expensive diagnostic options and or helps avoid unwarranted therapy).

The Leapfrog Innovator positioning is primarily designed to creatively destruct any incumbent caught sleeping at the wheel (if something is valuable, it’s worth doing better (aka, causing a substitution)). It is NOT the standard advice for new entrants – It is a strategy most often followed by incumbents with deep pockets, either leapfrogging their given arch-rival in their industry (Pratt & Whitney vs. GE in Jet Engines), or invading someone else’s territory (Apple entering the smart-phone business invented (and fumbled) by BlackBerry et al.). A Leapfrog strategy caters to the under-served customers of incumbents (thus, an attack from the top, vs. an attack from the bottom in the Disruptive model). A new entrant can follow this strategy provided it has the proverbial ‘10X’ advantage in either technology or customer experience. Fred Sanger’s sequencer provided a ‘1000 X’ improvement over other methods of reading the single bases that make up our DNA – an advantage held for 25 years until the coming of Next Gen Sequencing. Do other Leapfroggers such as Qualcomm, Dyson, Tesla, Patron or Wholefoods have the same advantage in their given markets? Time will tell.

The Fast Follower positioning is primarily designed to take advantage of someone else’s pioneering efforts and ride a rising tide (if something is valuable, it’s worth copying). It is also NOT the standard advice for new entrants – This is also a strategy most often followed by incumbents with deep pockets (and other structural advantages in place), such as Samsung in smartphones and tablets. Having said that, it is inevitable for a lot of startups to fall under this category as competition is usually around somewhere, especially in new ‘gold rush’ opportunities – It matters less if there isn’t a clear leader of the pack, of course, where execution details can make the difference (Facebook vs. MySpace provides a good example of where being a fast follower or being first to market in an undefined arena is largely a grey matter). Another variant of this strategy is to be a fast, sub-follower; think pilot fish to a shark, not a blood-sucking leech 🙂 – for example, quickly jump onboard a rising platform as one of the first tenants – e.g. Zynga/Facebook, PayPal/Ebay, PrimeSense/MS XBox).

Those that are not big fans of ‘strategy as theory’ often overlook the Competitive Positioning choice. Some say it’s impractical to follow as one can never truly anticipate the moves of competitors or know about competitors that may or may not be lurking around the corner. Other’s say that there isn’t really a choice of positioning, once the market and the business model has been chosen – However, everyone admits that the chosen target customer has free-will and will look at one’s offering as it compares to that of other providers (or indirect substitutes for the same need) – Ironically, when the opportunity is seen through a customer-centric lens, it can become more clear how to differentiate from competitors, back-tracking into positioning theory (as well as influencing company building, business model and integration choices).

6. Product Scope

- Single vs. Multiple Products (or Services)

- Breath vs. Depth of Features

- Source of Novelty

The Single vs. Multiple Products choice isn’t simply a matter of tactics. You take on too much too soon, you could run out of runway, or worse yet, obfuscate your value proposition. But on the flip side, you don’t provide enough reason for someone to ‘enter’ your physical or virtual ‘showroom’, and your never really had a chance to transact (with enough frequency, with enough customers). Like it or not, some markets require variety, others a complete solution to a given problem. So you should think not ‘Minimum Viable Product’ but ‘Minimum Viable Proposition’ that addresses either the need for variety or the need for a complete solution.

Local San Diego startup HouseCall struggled with the first half of this choice early on – Should it offer to match supply and demand for home services via an LBS mobile app in a particular category only, such as tech installation help, or cover a wide variety of home maintenance services incl. security, handyman, painting, maid services, smart-home, etc.? HouseCall chose the latter as a better chance to grow its customer base fast, despite the added effort on signing up suppliers.

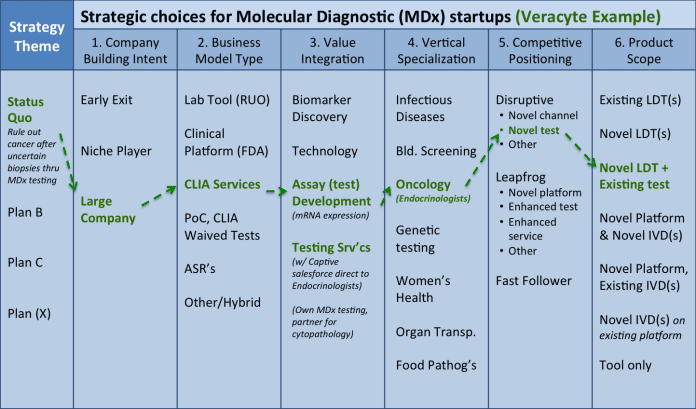

Cancer diagnostics darling Veracyte struggled with the second half of this choice. It offered a novel molecular test for thyroid cancer but the endocrinologists that it targeted wanted a one-stop shop solution covering both the FNA (Fine Needle Aspirate) cytopathology report and the follow-up molecular test (did not want to perform two biopsies and or deal w/ two labs, i.e. didn’t see things as two separate problems). Veracyte realized what its MVP had to become a turnkey solution covering a complete FNA biopsy. (Related to category #3 above, Veracyte partnered with a company called TCP to outsource its cytopathology lab capacity needs, but it maintains the single relationship w/the doctors, i.e. kept control).

The Breadth vs. Depth of Features choice also isn’t a simple matter of tactics. Within a given offering, be it a product or service, feature creep can certainly derail your efforts, resulting in some sort of Frankenstein concoction that no one understands or values enough to use or pay the money you’re expecting to recover your costs. But you shouldn’t simply view things in terms of how many features you should build – It’s how many features and the depth of complexity in each feature that is necessary to realize your minimum viable proposition (that completely solves a single problem) in the mind of the end user/customer. This exercise cannot be done in the absence of truly understanding what it is you’re really selling, including the emotional aspects of ‘problems’ (I’ll cover the set of deep value propositions in a future blog). Steve Jobs obsessed about design details because he was selling an aspirational product, not simply a productivity enhancer.

HouseCall decided not to provide a fixed or auction style price to match contractor supply with homeowner demand and let individual contractors set their own price (as this feature would have required extensive effort and wasn’t critical to its minimum viable proposition of “help when you want it most”). However, its real-time location-matching algorithm is state of the art. Veracyte likewise focuses on a single proposition (reducing indeterminate cytopathology reports), but Veracyte’s technology is likewise comprehensive, based on researching the whole human genome and selecting a whopping number of 142 genes for its algorithm to maximize the test’s sensitivity and specificity.

our Source of Novelty choice can get lost when discussing the offering and feature scope. Your novelty could be the product or service itself or a killer feature no one had bothered to include in an existing category. But the novelty can also be in other aspects of the business model, for example the channel. You might need a bundled offering to convince customers to try you out, but not all of the components need be novel – However, there should at least be ONE source of novelty in your concept, and careful to take on too many sources at once: It’s not hard doing two or more things at once, it’s hard doing two or more novel things at once. So in the examples above, the source of novelty for HouseCall is its smartphone approach to ‘Angie’s List’ (They’re not making up new categories of home-services) and in the case of Veracyte, it’s their molecular assay itself, not the initial FNA biopsy and not the centralized CLIA lab business model. Another famous example is Facebook’s News Feed feature – A fast follower to MySpace or not, you gotta give credit to Facebook for this novelty – it changed social networking from staying in touch to addictive (not claiming healthy) must-watch voyeurism, err…entertainment.

Perhaps Albert Einstein put it best to describe the Product Scope choices when he reportedly said: “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

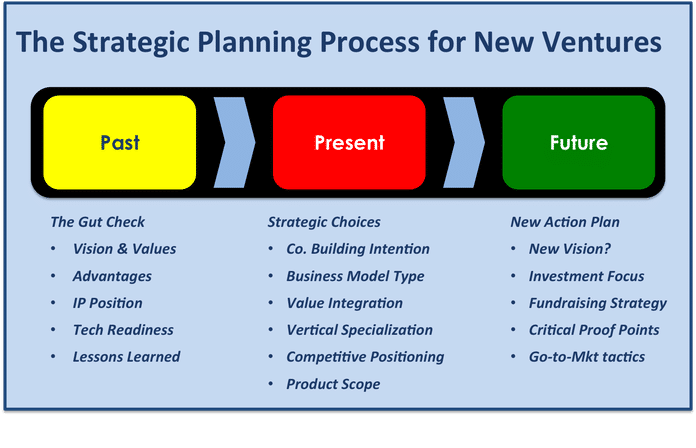

Summary

The strategic choice framework above is meant to guide a discussion on new venture strategy, not provide a magic-bullet answer to every conundrum. Having said that, I do firmly believe that startups and innovation projects fail for no greater reason than poor strategy – the wrong preparation and/or dynamism before and during battle. The framework I’ve presented is of course useless without a prior understanding of strategy, a company specific assessment of its own stark reality, and a commitment to change as needed. It will be hard to appreciate this or any framework without prior battle experience (within the same venture) – strategic planning is recommended after you’ve been ‘punched in the mouth’, not at the business plan stage (if you’re still writing those).

An honest assessment or ‘Gut Check’ of the situation to date (The Past) followed by careful consideration of strategic choices through an organized framework (The Present) should in principle put the startup or innovation team in a better frame of mind to make the set of commitments and actions that follow (The Future), including:

- New Vision or renewed pledge to the old vision

- Investment focus or shift (of resources and cash on hand)

- Fund raising needs and sources (fundraising strategy)

- Critical Proof Points vs. development emphasis

- Various tactical, go-to-market considerations

So, putting it all together, a strategic planning process for new ventures looks as follows:

A useful way to conduct a strat plan exercise AS A TEAM is to use a Strategic Choice Canvas tailored to your given industry or market arena, such as the one provided below for the molecular diagnostics space. As in any discussion trying to profit from the various opinions of others, it is useful to draw up different alternatives and discuss their implications before settling on any one pre-determined path and or choosing a hybrid approach. You may also choose to include a couple of tactical choices as integral to the strategic discussion (while you have the right people together including your board advisors), such as the spending focus or shift for the remaining cash, ahead of new rounds of funding.

Acknowledgements on this piece:

I learned the little that I know about new venture strategy from leaders and mentors I had the opportunity to work with at various startups and consulting firms and especially when running Qualcomm’s Venture Fest accelerator program. These include BCG’s Rob Davies, Luis Gravito & Rob Lachenauer, BTG’s Steven Shiller & Nkere Udofia, Mobilocity’s Omar Javaid, SDSU’s Alex de Noble, Global Connect’s Sandy Ehrlich, MIT’s Bill Aulet & Tom Malone, LMU’s Martin Spann, Cameron & Associates Ron Pierantozzi & Alex van Putten, Lean Entrepreneur’s Brant Cooper, Core Strategy’s Mark Long, Agile Strategy’s Michael Lurie, IDEO’s Dave Blakely & Hans Haenlein, Qualcomm’s own executives Paul Jacobs, Irwin Jacobs, Steve Altman, Peggy Johnson, Roger Martin, Len Lauer, Bill Keitel, Franklin Antonio and Matt Grob, Qualcomm spin-offs Mike Yuen (Zeebo), Ian Heidt (HouseCall), Sharad Pawar (BeWo), Adam Riggs-Zeigen (RockMyWorld), Clarence Chui (Outward), K+S Ranch’s Steve Blank & Bob Dorf and Biological Dynamics Raj Krishnan, David Charlot and Francois Ferre. Thank you for the lessons (through kindness or berating)!

Ricardo dos Santos

Ricardo dos Santos is a leading expert on entrepreneurship and corporate innovation, having amassed more than 20 years experience driving internal ventures at major corporations and launching early stage startups. In 2012, Ricardo brought that experience and his vast knowledge of the Customer Development methodology he learned directly under startup expert Steve Blank to Biological Dynamics, a molecular diagnostics startup focused on the oncology market. Before joining the executive team at Biological Dynamics, Ricardo helped set the standard for successful corporate accelerators as the senior director of business development at Qualcomm. He is a lecturer at San Diego State University, teaching courses on Entrepreneurship and Innovation and he is also a part-time speaker and advisor on Lean Innovation to Fortune 500 companies.