The Question of Efficiency

This article addresses the last of the four critical questions for strategic portfolio decisions (see below), efficiency. The prior three questions — sufficiency, significance and renewal — are fundamentally questions of effectiveness, which must always proceed the question of efficiency.

“There is nothing so useless as doing efficiently that which should not be done at all.”

– Peter Drucker

Portfolio theory and portfolio analysts often skip over effectiveness and look at an efficiency measure like return on investment to “optimize” the portfolio. This logic is mathematically impeccable: if you want to get the most return for a given level of investment, invest in the order of return, from highest to lowest. This logic is also naïve, and doesn’t drive practical decision making.

The practical version of this question is “Are we being good stewards of our resources?” Executives need to ask “Are we deploying our resources to their highest and best use, or alternatively are we getting good value for money?”

A Practical Tool to Start Efficiency Conversations

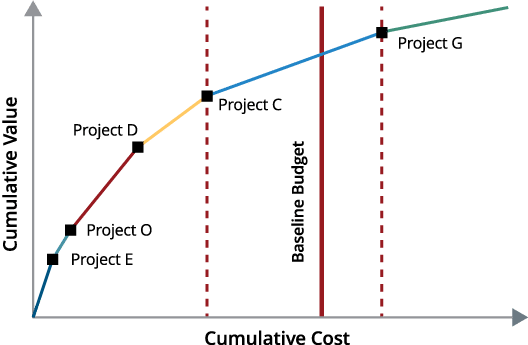

One tool to address this question is the CFO chart, which shows cumulative investment on the X axis and cumulative value on the Y axis—the basic financial inputs and outputs.

Each project is shown as a “lollipop” stacked upon its predecessor. The slope of the line gives you the return on investment of the project (steeper means higher return), and the length of the lollipop stick shows the incremental investment and value of that project. Ordering the projects from highest ROI to lowest causes the overall curve to flatten. The curve also shows a sort of 80/20 rule—most of the value comes from relatively few projects.

The naïve reading of this chart is to pick a budget on the X axis, go up to the curve, and fund all the high-return projects to the left. This gives the portfolio value indicated on the Y axis. The projects to the right of the line, with low returns, should be shelved or canceled (see Five Ways to Say ‘No’). From a numbers standpoint, this portfolio is the best you can do for that investment budget.

No executive in their right mind would commit their organization just because an algorithm said so. People make decisions of this sort, not algorithms. Fear of an algorithm dictating decisions creates a lot of dysfunctional decision behaviors in organizations.

Still, the naïve recommendation is a good place to start discussions because it is neutral and clear, and gives a starting point which is NOT the status quo. Inevitably some pet projects are not on the list, while some surprising projects are on it. This contrast creates a kind of organizational tension which drives executives to question their assumptions and really look in a more honest way at whether they are being good stewards of their resources.

Conducting the Efficiency Conversation

If an executive wants to fund a project that has a relatively low return, that invites the question, why?

- A first reason might be effectiveness: it is required to deliver on sufficiency or renewal.

- A second reason might be strategic: the choice reflects value not modelled in the project evaluation. No model is complete, and executives often have good judgement for situations that no model could ever capture for all projects. A common example is doing a low-return project as a favor to a hugely important account. Or executives may have the intention to create a new future, for example, with projects that create a desired safety culture or that probe into a new market to learn how to enter a new line of business. A project evaluation model always leaves something unaccounted (and it is a fool’s errand to try to model everything).

Opportunity Cost and the Cost of Opportunities

Efficiency and strategy are best addressed through opportunity cost. If you want to fund a project that has low ROI, what other project has to be displaced? The value of this foregone opportunity is the implicit cost of your strategic choice, and it has a clear dollar value.

For example, let’s say you want to fund a project that returns $1M. Suppose that on the CFO chart’s naïve funding list, this project shouldn’t be funded. So choosing to pursue it will displace something. Let’s say the displaced project would have returned $10M. This means the opportunity cost of the strategic choice is $9M. The real question is whether your “strategy” is worth an investment of $9M.

This completely reframes the question and helps executives power through difficult choices. The proposed “strategic” project either is or is not worth its opportunity cost. If it is, choose the project with the confidence that you are being a good steward of your resources. If it is not, walk away, no matter how much attachment you feel to the project.

The portfolio that results from modifying the naïve portfolio with these effectiveness and strategic questions will be the portfolio that delivers results (effectiveness and strategy) with the greatest return (efficiency) at a given level of investment. You will be surprised: most companies find they can accomplish the same results at 30% greater returns, sometimes two to three times the return (or alternatively at substantially less investment). Efficiency matters, even if it is not the first consideration.

Once you have this kind of clarity, you may be in for another pleasant surprise. There are always projects “on the margin”, in that you cannot quite fund them at a given level of investment. Or perhaps you are constrained by a non-financial resource, like marketing or technical headcount, and just a bit more would let you fund an additional high-return project.

The same “opportunity cost” thinking will give you tremendous insight into what the right investment level should be. Portfolios decisions are all made given a level of investment (dollars or other constrained resources). The value and return of the project you cannot quite fund tells you whether you should increase budgets or otherwise invest to change the constraints. Once you have real clarity into the return on investment, you see value of changing the constraints.

In innovation portfolios for example, opportunity cost thinking often shows executives where they’re missing some of the best investment opportunities available to the company. Change the budget. Cut back projects with lesser returns. Hire or contract to relieve critical resource constraints. Executives have crucial decisions to make about the portfolio beyond yes/no or prioritizing projects. The efficiency question can bring these other types of choices productively into play. Demonstrating that you are a good steward of resources by using tools like the CFO chart and tackling efficiency head on with objectivity and rigor can convert scarcity into abundance.

Four critical questions for decision making in strategic portfolio management

Sufficiency: Do we have enough to achieve our goals?

Significance: Are we focusing on things that matter?

Renewal: Can we thrive in the future?

Efficiency: Are we being good stewards of our resources?