“I had never felt so badly about creating a success,” Michael, the CTO told me.

He was in charge of a large R&D organization and he had a very cool, slightly quirky technology. He asked for many proposals for how to exploit it. Every time the financials came in, it just wasn’t enough. Under pressure to deliver, he picked the proposal that looked the most reliable: they licensed out most of the technology. The ROI was fabulous, and Michael was praised for it.

“When I saw a few years later that the technology had become the web browser, I knew things were broken. We missed the biggest opportunity of a generation and managed to justify it to ourselves, even celebrate our insignificant results. At that point I made a personal commitment to do what was right for the company, even if our systems got in the way.”

While not every missed opportunity is as large as the web browser, the pattern is prevalent among companies. Here is how things go wrong.

Most evaluations in a company are done based on a promise. You make a bunch of “reasonable” assumptions about your project and create financial projections in a spreadsheet. These assumptions are negotiated until you find a financial case that you can promise. Funding is given based on accountability to this financial promise, and funding is released over time based on progress towards the promise enshrined in the spreadsheet.

Establishing the Right Promise

Establishing the right promise is a delicate art. Promise too much and you will fall short, ruining your reputation; promise too little and it won’t justify the investment. Many companies find a sort of compromise, promising the bare minimum to get investment and then arguing for the project based on “strategic” reasons. For example, one might argue that the first project is a stepping stone to other opportunities, or gets us a toehold in a major market, or perhaps that the promise represents a value we want to promote. “Under promise and over deliver” is the usual mantra.

Then a huge amount of effort goes into scrutinizing and tracking the details of the promise. The spreadsheet that models the promise often calculates it to an absurd level of precision: who cares about the third decimal place on third year sales? Requiring this precision forces your staff to amass a large amount of evidence to support the promised case, which creates lots of work and documentation.

We have a habit of treating the spreadsheet promise as if it were real, as if managing to the spreadsheet is managing the company and making good decisions. The dangerous part of this habit is that sometimes we take the promise so seriously it become a self-fulfilling prophesy, and we get merely the results promised, that is, the minimum promise we could get away with to support the funding. Rarely is this the full value of the opportunity.

Some projects do in fact over-deliver on their small promises, and we celebrate the achievement. This small success validates the method and makes us feel good about the whole process. But it is a consolation prize, masking a massive opportunity that has been lost.

This unintended mediocrity created by a minimum promise is a very big deal. It can commonly reduce the opportunity by a factor of four or five.

Example project

Here is an example from a project in agriculture. These projects have long time frames, so you can see how the pattern plays out as each successive evaluation is completed. It works the same in other industries, it is just harder to see it happen.

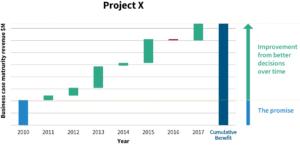

The original evaluation for Project X was done in 2010, and the graph below summarizes the financials in terms of revenue at maturity. This was the promise.

Had this company relied solely on the value in the spreadsheet, they would have ultimately delivered the promise. However, for this company, they looked beyond the spreadsheet. Their evaluations were not based on an agreed set of assumptions. They considered many different scenarios, both upside and downside. They had a tangible and clear understanding not of just what the project was worth on the spreadsheet, but on what factors drove the value in the spreadsheet.

This tangibility of the upside and downside is the key. It allows the decision to invest to be made in ways that are subtle but profoundly more powerful than the traditional method.

First, the reliable promise is selected AFTER the range of uncertain futures is well understood. The promise then represents what we can reliably deliver given everything we know today. It does not reflect the value of the project, just what we can promise now. This is opposite from the usual method, where the promise is negotiated to produce an evaluation that wrongly becomes our main view of our future prospects.

Second, with a tangible view of what exactly creates the upside, the company creatively pursues projects explicitly designed to find it. Can we find a way to convert this currently speculative upside into something reliable? What would we have to learn to drive the project to deliver much better results?

In the traditional method, funding is released to accomplish the promise. For this company, funding is also released to explore and deliver on the upside.

The impact of this shift in evaluation and changes in decision making is visible on the graphic. In 2011, the company finds ways to make the project a little better. In 2012, they get some bigger ideas. In 2013 they find a major way to improve it. Even the small setback in 2016 is dwarfed by the year-to-year improvements. Each year, the company refines its decisions about where and how much to invest to keep the project moving forward.

The cumulative effect of these improvements created by seeking the upside and making ever better decisions is quadruple the original promise! In other words, it would take four projects operating at the promise level to match the performance of this one. I am not saying this will happen to every project, but it will happen to many of them.

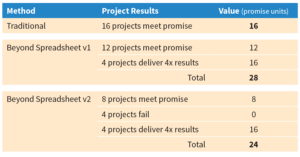

Let’s put that into portfolio terms. Suppose you had a portfolio of 16 projects. If you pursue only the promise of the value IN the spreadsheet, you will get a result of 16 units of promised value. Now suppose you pursue the value BEYOND the spreadsheet. Let’s just say that a quarter of the projects see the kinds of benefits in Project X. Then the result will be worth 28 units, almost double the original portfolio value, as shown in this table.

Even if you thought the Beyond Spreadsheet method would somehow damage projects, it is still a better method to use. For example, let’s take a sceptic’s scenario (v2) and suppose that additionally a quarter of the projects fail outright as a result. The portfolio performance is still 24 units, a full 50% higher than the traditional method.

The frightening thing about the traditional method is that it hides the evidence of its own weakness. So you can go on with the familiar approach and celebrate mediocre successes. Or you can see, like Michael the CTO, that there is a better way, and make a commitment to do what is right for the company. The current approach may get in the way. So maybe it is time to change it.

Seek the unpromised value beyond the spreadsheet.