Reliable Promises Create Mediocrity

By David Matheson  19 min read

19 min read

“They’ve been sandbagging me,” the president of a multi-billion-dollar company exclaimed when I showed her a summary of the upsides in the growth portfolio.

After years of declining growth and spending more and more “fighting the fade” of revenue in the core business, she had decided she needed to revitalize innovation. As part of that effort, they were deploying a Strategic Portfolio Management process in the organization. The objective was to find opportunities with more meaningful impact and to improve the business processes so that they could deliver such opportunities less haphazardly. This meeting was my opportunity to share the results on the first complete view of the portfolio.

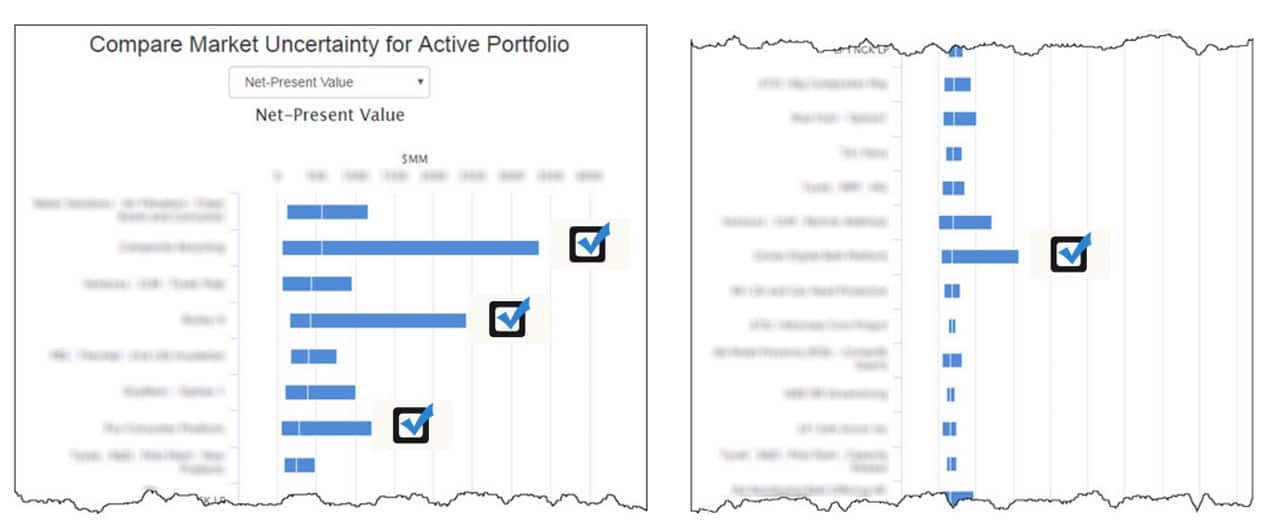

The chart that had caught her attention showed the upside and downside uncertainty in the business cases for about a hundred innovation projects that the company was pursuing [Figure 1]. For most of the projects, the range of uncertainty was relatively narrow. But for about one in five of the projects, the upsides were massive—if pursued correctly and with a little luck, some of them could produce 10x the returns in the base business case. We had found hidden growth opportunities nascent in the current set of projects!

Figure 1: About 1 in 5 projects have significant upside.

But she didn’t seem happy, she seemed frustrated. She sprang into action mode, “What do I need to hold these project teams accountable to?” She thought for a moment, “I’ll just reset the teams’ goals to the upside and get them to commit to a bigger number.” You could almost see her adding up the newly imagined commitment numbers in her mind, and it was producing a financial plan she liked.

Her operational instinct, to focus on creating accountability and demanding the financial commitment of her teams, is a common way to run a company. But I could see that this was going to be problematic and might even be a hint as to why the company found itself in a declining growth mode for the last few years.

I ventured, “I think that might backfire.”

Without intending to, she had sent very mixed messages to her organization, as many executives do. Over the past year she had exhorted them to innovate boldly and come up with ideas that would move the needle in the business. At the same time, by focusing on the reliable promise, she created pressures that drove leaders to seek safety, resulting in them systematically thinking small and incrementally. Her ability to lead the organization to more growth rested in unwinding this mixed message and giving her teams a path forward.

Her challenge was to create visibility to the big idea and then use her business processes to drive her teams to seek the upside rather than promise it. One of the most powerful but subtle benefits of Strategic Portfolio Management is the ability to improve critical thinking about growth at the project level. But the usual Operational Portfolio Management can get in the way.

The traditional approach to portfolio management is very focused on selecting the right projects. It’s positioned as a tool for executives, who review insightful displays and dashboards to make tradeoffs about benefits (like financial return and accomplishing strategy) against costs (like investment, resources and risks). The “data” from projects represents more or less promises the leaders have made about what they can deliver, usually including financial metrics with various caveats on “risk” or “fit to strategy” or other softer topics. Periodically the executives review the portfolio, tweak and bless the prioritization of projects, and make decisions.

This part of the portfolio management process is not wrong; it’s just radically incomplete and misses a very important part of the portfolio process: making projects better. As a result, the traditional approach has many unintended consequences that often make projects worse. As projects become worse, good choices become sparse, the portfolio becomes mediocre, and growth suffers.

I’ve seen two major unintended consequences of this operational view of portfolio management:

The typical portfolio process has two steps: (1) gather data and (2) make decisions. In the gather data step, executives basically ask each project manager to give you a set of estimates about their project’s cost, schedule, and returns. In addition, executives want the project manager to provide supporting data to validate those estimates. The estimates and the data will form the basis of your project prioritization and ultimate portfolio selections.

It seems like a straightforward and benign data request. But it isn’t.

For the project teams, this is a very stressful exercise because their projects are on the line. The best outcome they can hope for is that their project lives on for another funding cycle. Another outcome is a real threat: the cancellation or de-prioritization of their project. As one project leader described it, “What you’re doing with this process is asking me for the rope you’re going to use to hang me.”

Project teams will therefore view requests for estimates and data as a compliance exercise, not as an opportunity for improving the project. Doing an evaluation seems like it should be an opportunity for critical thinking—reflecting on the assumptions and what has been learned, stepping back to get a broader perspective, and finding the best way forward now. But it rarely works out this way. Most project teams will respond to the fear the request induces by skewing or adjusting their estimates and data to increase their perceived chances of keeping their projects going, either unintentionally through natural human cognitive bias or intentionally as a political survival strategy.

“What you’re doing with this process is asking me for the rope you’re going to use to hang me.”

Teams have a difficult political tension to manage. To the extent the evaluation is a promise, they want to keep it small so they can reliably deliver. But if it’s too small, then the project doesn’t seem like it’s worth doing. So, the resulting evaluation is heavily colored by the political situation the team faces. Ideally, the team can find a handwavy way to indicate large potential and get people excited but still keep their promises small. Or lobby for an evaluation process based on subjective criteria that favors their project but doesn’t force them to make a big promise.

The result at the portfolio level is often a set of pretty charts arranged in a dashboard that displays all this information. Executives treat these charts as if they basically reflect the merits of the project. But that basic assumption is often wrong. Often the charts reflect the political situation the teams face. At the end of the day, these distortions at the project level translate into poorly informed decisions at the portfolio level, dressed up as “data”.

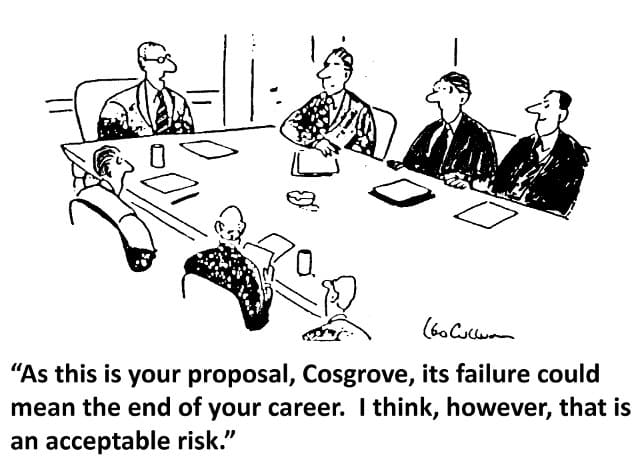

For many project leaders, the pressure can be intense because it’s more than just the survival of the project at stake, it’s the survival of one’s reputation. Who is really at risk if a team proposes a bold innovation in response to an executive exhortation? From an organizational viewpoint, let’s assume that the proposal is a good one and represents an excellently calculated risk for the company. If the project fails or stumbles or falls short, then accountability puts an angry spotlight on the team or its leader. It’s too much of a risk for the individuals. The operational approach creates a situation where risks that are good for the company are transferred to the individual, who cannot bear them, as shown in Figure 2. This transfer of risk distorts estimation, evaluation and decision making.

Figure 2

One of the social pressures on project teams is to be seen as meeting their promises. If a project manager always meets his or her estimates and gets results that match the supporting data, that manager gains a reputation for accurate forecasting. In future planning cycles, the executive management will be more inclined to take that project manager at his or her word and fund the projects. And that project manager’s reputation rises with management because they offer two things management prizes highly: predictability and efficiency.

The desire to be seen as a maker of reliable promises creates an incentive to make promises that are easy to keep. Unfortunately, that leads many project managers to fiddle with their teams’ estimates and data, water them down and amputate the upside. They limit the returns they promise because they want to ensure they can deliver on their promises.

But predictability and efficiency are not goals of an innovation portfolio; growth and rejuvenation are. An innovation portfolio that reliably turns out small economic returns through incremental change will not sustain the business in the long run. How to encourage people to find big upsides and work towards them?

The president was sincere in her exhortations for teams to innovate boldly. And the organization had a long tradition of growth through innovation. For decades, this company had attracted great talent who wanted to change the world. It was clear that many projects were wrapped in a “strategic” mantle describing a big dream that would create prosperity and growth for the company and its customers. It was inspiring.

Yet when projects faced evaluation, many were very small, barely justifiable in financial terms. There was a vast gap between the evaluation implied by the big dream, and the actual evaluation submitted. Consequently, teams tended to promote their projects based on the dreams, making handwavy “strategic” arguments, rather than on the merits of their actual proposal.

It’s a consequence of the focus on survival, making promises you can keep and having reliable business cases. Having small business cases against big dreams is bad enough, but the real issue is deeper: these small projects have no real prospects of achieving the big dream.

The main problem is there isn’t much discussion about what it takes to create the dream. Rather the focus is on what we can promise now. In particular, without an evaluation of the big dream, there was little insight into what had to be true to create it. Consequently, many projects leave the most important factors up to chance.

There was a vast gap between the evaluation implied by the big dream, and the actual evaluation submitted.

Here’s a real-life example: Frequency-hopping radios are an important part of the future of military radios. The necessary large antennas on vehicles make them a clear target as command vehicles for the bad guys. So how to make the antennas small enough so they are less visible and more portable?

At its core, it’s a materials problem. Making materials for the circuitry that are transparent to a wide range of frequencies of radio is very challenging. The company working on this was best-in-class at this sort of problem and was doing pilots with the Army Rangers that incorporated a new material into the antenna.

The project was essentially a proof of concept for military vehicles, a materials qualification and a field test with an important customer. It had all the hallmarks of a great project: big strategic problem, clear defendable value-added technology, customer validation and interest. It’s a big dream wrapped in a compelling strategic mantle. Seems like it should be a real winner!

The problems became clear was when finance looked at the project. Finance made reasonable assumptions about the business prospects assuming that the team eventually passed the Army Rangers’ tests. The Rangers place orders for vehicles with these radios, specifying the new material for the antennas based on the field-tested designs. They start with some vehicles, and slowly increase orders over time. Each order pulls through some premium priced material. Other military buyers see the success of the Rangers’ vehicles and consider ordering vehicles themselves and eventually specify the new material for their orders. And so on. The whole process is slow and limited by the rate of vehicle orders by various customers and design cycles of vehicles and radios. The bottom line:

Instead of justifying this small project based on “strategic” considerations, they took a more constructive approach and re-evaluated the uncertainty in the project from the point of view of the big dream. What they realized is that the business success of the project—achieving the big dream—required the standardization of this new material by radio and vehicle manufacturers. If they could figure out a way to get these players to incorporate the new material into all of their products, then they would reach a vast market quickly. Ideally, all new vehicle orders, by any customer would simply come with the frequency-hopping radios based on the new material as standard. There was no slow buildup of customer awareness to order this special radio, and no long design cycles as the new material was specified into a series of orders.

But the current project had left all this up to chance. There was simply no attention going into the issues around radio and vehicle manufacturers or standards or anything like this. A project crafted to deliver on the full dream needs to include innovations on influencing the buying behavior of vehicle and radio manufacturers. The actual project had a complete blind spot in this critical area: no plans, no staff skilled in these issues, nothing! So, this big dream of transforming frequency hopping radios was trapped in the small project of materials qualification, which had little chance of achieving the dream.

Not only does the promise-focused approach hide this sort of business insight, it also unintentionally encourages the project team to play it safe even if their safety results in mediocrity for the company.

In this example, the project team, which largely consists of materials scientists, got to stay in their comfort zone of materials. Further, they could say “we did our part” in qualifying the material. By making their reliable promise—delivering on the materials, it distracted from the larger question of what would it take to actually make this project a real winner?

The question isn’t “what can you promise” the question is “what does it take to grow”. The operational approach makes it too easy to substitute one question for the other. Everyone goes along because they are seeking safety and making the promises they can keep.

We have this dream of doing something big and important, but the business process we’re in actually makes it mediocre. What to do about it?

Operational portfolio management focuses on predictability and efficiency. By contrast, Strategic Portfolio Management takes a different view. It’s explicitly focused on the question of “how to grow?” The “hidden” part of the portfolio process pushes this question in a meaningful way into the project level. This hidden part of the portfolio process has huge leverage and creates a virtuous cycle of better projects, leading to better portfolio choices, leading to growth. Less of the resources are spent fighting the fade, which leaves more resources available for creating better projects.

Having seen many portfolio processes, my rough guess is that about 2/3 of the benefit is from improving the projects and only 1/3 from better project selection. Traditional operational portfolio processes are focused on prioritization—the selection of projects—which misses most of the benefit. It isn’t just “yes or no”; it’s “how to grow”.

I’ve already hinted at how to find the obstacle to the big dream in the frequency hopping radio example above. By evaluating the project and its upside and downside uncertainties from the point of view of the big dream (not the reliable promise), the materials team gained real insight into what it would take to create that big dream.

To address the obstacle, they supplemented the materials qualification project with a business development project targeting the radio and vehicle manufactures. They called it “the upside exploitation plan” and assigned appropriate resources to pursue it. This included top executive level communication between the materials company and radio and vehicle manufacturers to get these partners on board with the Army Rangers pilot, the sort of move that would never have been imagined before.

The key to finding and addressing obstacles is to use the evaluation step in a portfolio process to give teams an opportunity to use evaluation to improve their critical thinking. It’s a completely different way of viewing the role of economic evaluation than in an operational portfolio. The “business case” isn’t a deliverable or a promise; it’s an active tool for innovation and insight. It’s a place to consolidate lessons learned, form a new view of the project, and ask anew “how to grow” with this project? What will most move the ball?

Use your Strategic Portfolio Management to insert a common standard for evaluation that encourages critical thinking and gives project teams better tools for doing so.

Every project leader has to go through a cycle: dream up some goal or target, make a plan to get it done, and evaluate whether their idea and plan is worth doing. Often the evaluation is haphazard, ranging from intuition that the idea is big enough to pursue, to discussions with colleagues about the merits of the approach, to formal analysis.

Use your Strategic Portfolio Management to insert a common standard for evaluation that encourages critical thinking and gives project teams better tools for doing so: shift the spirit of the required evaluation question from “Justify my project” to “How do I make my project great?”

Most evaluation and financial systems set the evaluation up as a data-gathering task rather than an exploration of what is really worth doing. Many of these project leaders aren’t trained in business or financial thinking, they have other skills. The typical business case request does very little to support a team leader to use evaluation as a tool for critical thinking. Their finance partners are usually just trying to collect data based on reasonable assumptions and have little training in thinking through big innovative dreams. So, most evaluation systems don’t do anything to help the project leaders figure out how to make their projects great.

Improving projects as part of the evaluation involves changing the standards or ground rules. First, we aren’t promising or even being reasonable. We are exploring. In the frequency hopping radio example, the reasonable evaluation from finance defined a project that simply wasn’t worth pursuing. Innovation required exploring the unreasonable outcomes, of shifting the radio standard, that we are trying to create.

Second, frame the evaluation from the point of view of the big dream. What are we really trying to do? What has to be true across the business case to make that happen? In the frequency hopping radio example, that line of thinking invited them to consider the business issues on their success path, specifically how orders cascade from the initial buyer (Army Rangers) through the value chain (radio and vehicle manufacturers) and then expand to other customers.

Third, look at ranges of uncertainty, particularly the upside. The big dream is undoubtedly unreasonable, an aspirational fiction. But by looking at the concrete scenarios for upside and downside on factors like price or share, teams get a lot of insight into innovation issues like customer willingness to pay, how we extract value from a transaction and competitiveness. These types of questions are central to any innovation, not merely business case assumptions. Use these insights to improve the project, and focus resources on the uncertainties that have a big impact on the business case.

This shift, from making promises to improving projects, might sound good. But it creates a problem in the reliability-oriented environment of operational thinking about the portfolio. What should you hold people accountable for?

Upon seeing the upside in many projects, the emotional reaction of the president I was presenting to was one of frustration, that her teams had been sandbagging her. Her initial response was to try holding them accountable for the newly revealed upside. That would have backfired, but what should she hold them accountable for?

Looking at this from the point of view of the project leader, they have actually made themselves vulnerable by exposing the upside. They have precisely exposed the ignorance gap between what they can promise now and where we would like to be. Further, they have quantified the ignorance gap, showing directly the financial implications of this uncertainty. This explicit upside lowers the predictability of the project! The project leader is out of his or her comfort zone, has exposed ignorance, and now has an unpredictable project. They are understandably worried about the safety of the project and his or her reputation.

One additional shift is required to unlock the hidden portfolio process. Make the strategic portfolio process Value-Seeking, not Promise-Delivering. Reframe the role of the evaluation as a compass— a direction you should be heading— rather than a specific destination.

For innovative projects, this shift can be liberating. To unleash an innovative opportunity, you may have to reallocate resources, putting more on driving the upside, not just delivering on the promise. It can be a worthwhile shift in resourcing because the upside value can dwarf the value of the small more reliable projects that no longer get funding.

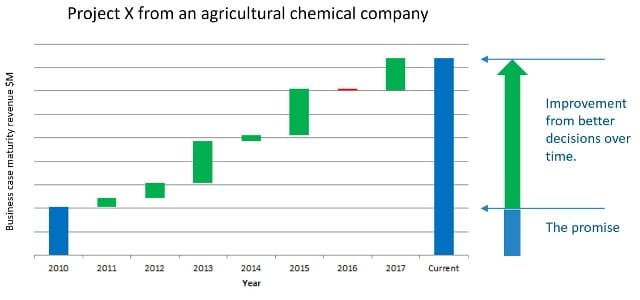

Here’s an example from an agricultural chemical company experience with “Project X” that they have evaluated and reevaluated over many years. They improved their project by 5X by being value-seeking.

Back in 2010, when this project was first launched, they made what they called “the baseline” of a financial outcome, how much revenue Project X would deliver. In developing the baseline, they conducted an uncertainty analysis and saw what factors were driving the upside of the business case. They asked relevant growth questions:

The resulting evaluation became a guide towards improvement and a measure of progress, relative to the baseline. Unlike other companies, they didn’t treat the baseline merely as a promise.

As the project evolved, in response to the “compass” created by the uncertainty analysis, they updated the evaluation of Project X every year, as shown in Figure 3. And so, in 2013, they figured out how to open up a new segment, and the project valuation went up. In 2015, they figured out how to improve their pricing model. In 2017, they figured out how to get more out of the value chain. The project evolved in a positive way, becoming value-seeking. The portfolio process encouraged these improvements and showed the results of new thinking over time. It wasn’t merely about delivering on the promise on an immutable project, it was about seeking more value and adapting the project (and its resourcing) accordingly.

Figure 3: It is better to be value-seeking than promise-delivering

This uncertainty range also made coordinating with downstream functions like manufacturing easier. Because manufacturing had a view into both the current thinking (“the baseline” and its evolution each year), as well as a view of the upside, they were better prepared to respond to a wide range of demand. They planned for the baseline view and developed contingencies for the upside (and downside scenarios). This communication was a big improvement, as this company had a history of underestimation in R&D, resulting in surprise shortages in manufacturing when the product did better than communicated. This dysfunctional situation was a win for R&D— we beat our promise—but a loss for manufacturing—a scramble to catch up to demand—and ultimately, a loss for the company due to lost opportunity.

This value-seeking approach caused about a 5X increase in the value of project X over time. Had they used a traditional promise-based system, they would have been delighted just to simply deliver on that, accepting only 1/5 of the project’s potential. (And maybe manufacturing would have been caught short). But, because the system was value-seeking, they actually got a 5X improvement.

Of course, sometimes a project may not increase in value, but rather falls short as the team learns more about the market, competition or technical performance. In a static world, the team often strives to deliver on a now-unattainable promise. I’ve seen projects last years beyond their expiry date, squandering millions just to show how committed they are. In this value-seeking world, the team adapts, quite possibly lowering their requested investment or in extreme cases canceling the project preemptively. The strategic portfolio process creates an opportunity to step back from operations, reflect, and adjust.

In Strategic Portfolio Management, investments are always for the next step, never the lifecycle of the project. If the project delivers evidence of the higher business case, it makes sense to increase the investment. If reality reveals itself that the project isn’t as promising as we hoped, the company has the opportunity to dial back. It’s a reduction of waste. Strategic Portfolio Management and the hidden process is dynamic, not a one-time decision.

If you apply this thinking across your entire portfolio, you will likely get push back. Many projects don’t actually have this sort of potential for improvement. My practical experience is probably about one in five projects in a typical portfolio have the potential for dramatic upside. But the impact on finding the upside on these few projects is massive across the portfolio. Here’s some simple math to illustrate: Suppose 1 in 5 projects have a 5x upside. This means that you can get the full benefit from the entire portfolio from just these projects. By focusing resources on these 20% of the projects and canceling or dialing back on the other 80% of the portfolio, you can get the same results. This focus will further reduce clutter and distraction, generally making operations easier as well.

These kind of benefits across a portfolio are generally invisible from the operational project-focused mindset. The operational focus is on getting the projects done, and may favor the 80% of the projects because that creates the most efficient process and highest throughput.

It’s actually inefficient to ask every project to look at its upside. It can be downright irritating for some project owners if, in fact, their projects are indeed small or not connected to bigger opportunities for growth. But if you don’t ask that of all your projects, you won’t find the big ones. And the leverage of finding the big ones is massive. Realizing this portfolio impact may be more important than getting many of the smaller projects executed.

In other words, Strategic Portfolio Management can unlock hidden growth potential. And while it may irritate owners of small projects, the benefits of such a process to the company can be significant.

Companies tend to optimize their processes for the majority of projects. Empirically, most projects have little upside. So, a common-sense approach to portfolio design will optimize for execution.

This is a mistake.

The paradox is that you want to optimize for growth, even if relatively few projects actually have the potential. The cost imposed on the small projects is dwarfed by the upside created by the growth projects.

My practical experience is probably about one in five projects in a typical portfolio have the potential for dramatic upside.

If you think of all those little projects meeting their little promises, it doesn’t take many projects to value-seek 5X to justify canceling lots of those little projects to reduce portfolio clutter. There’s a massive kind of portfolio effect here that’s quite surprising. Value-seeking is better from a strategic portfolio perspective than promise-keeping.

The president was concerned that her project leaders were sandbagging her, and had asked me if she could hold them accountable to the newly discovered upside. I ventured, “I think that might backfire.”

This caused her to pause. One of those pauses where you rethink your real objectives. I continued “Do you want a lot of projects to deliver predicable results, or do you want to discover an unreasonable upside that could create a new round of growth?”.

Her response was immediate, “We need new growth”.

“Then give your project leaders the tools they need to dream big and a compass to steer them towards that unreasonable upside. If a few only work out, you will meet and exceed your growth goals, even if a lot of the projects fail.”

That was a new insight for the president.

Corporate renewal isn’t easy or predictable. But we do know that easy and predictable won’t lead to growth. Reliable promises create mediocrity. To create growth: Think big. Improve projects. Become value-seeking. Harness the hidden process in Strategic Portfolio Management.