At a recent innovation conference, Henry Bryndza of DuPont reported on how they had improved the returns of their innovation across the portfolio by 2-3 times. But was this a fluke, a one-off result due to their particular circumstances? Or would applying the methods that Henry used result in similar benefits for other companies?

At a recent workshop, a group of about 35 R&D and innovation executives from industries ranging from Automotive to Google to Chemicals came together and explored this question. Each selected a real example project from their portfolio and applied an estimation model based on DuPont’s benchmarks and experience.

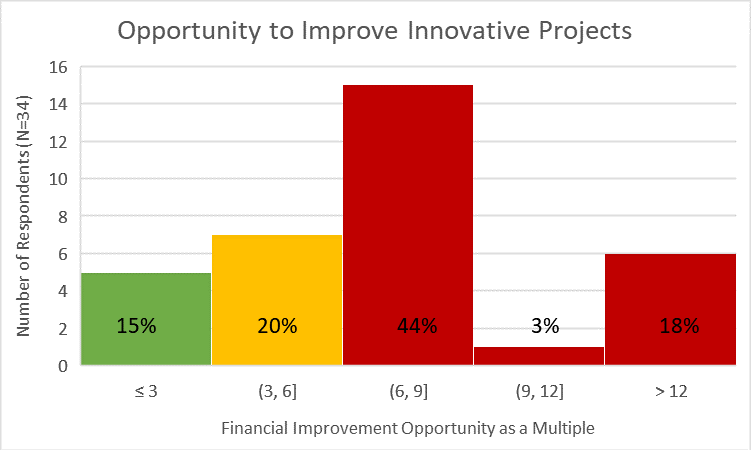

The average improvement opportunity across this diverse group was 8.1 times the current return on innovation. It is not a fluke: the improvement that DuPont found is available to most companies.

Only 15% of the group found improvement opportunities for their selected project to be 3 times or less. If the projects in your portfolio all have improvement potentials in this range, then you are doing well. Said another way, this means 85% of sample projects have a 3 times or more improvement opportunity.

20% of the participants found improvement potential between 3 and 6 times. While this is substantial, perhaps the projects selected have a greater improvement than typical in the portfolio, and so not much change is called for. Simply see you if you can find projects like this and make special cases of them.

However, a full 65% of the participants found improvements in their sample projects greater than 6 times! 18% found improvements great than 12 times! These improvements are worth rethinking your business process to discover and deliver upon. A few improvements like this across the portfolio justifies significant change, the returns are easily worth any imagined losses from shifting the status quo. (When you are ready to try out the assessment for yourself on an example project of your own, go to the Innovation Opportunity Factor Calculator.)

Most participants were surprised by the improvement potential from their sample project, just as DuPont was surprised when they realized the size of improvements across the portfolio. There is something about the status quo of evaluating innovation that obscures innovation’s true potential and makes it difficult for companies to realize how much they are leaving on the table.

DuPont’s basic insight was that the unintended consequences of good project management systematically undermined the value of their innovation projects. Specifically, there were two effects: they overlooked hidden upside, and they inadvertently wounded innovation projects by not giving them enough resources or attention.

Overlooking Hidden Upside

The traditional standard for evaluation is often “reliable delivery” or “the promise”. That is, projects are evaluated by what returns would be generated by reasonable assumptions given the development of the appropriate technology or offering.

The unintended consequence at DuPont was an ironic celebration of mediocrity, with business cases showing not what was possible, but rather, the bare minimum achievable. Projects were so focused on delivering these small (but reliable) results that they never had any visibility into what would make the results truly spectacular. Innovation in many cases is the attempt to create unreasonable returns, but these big dreams were never made tangible. This standard of evaluation created a self-fulfilling prophesy in which teams focused on small safe gains and achieved them, and therefore never delivered on a big return.

For example, customer interest was a real bonus. But sadly, project teams often misinterpreted the exciting signal of a specific customer’s interest as a measure of total market interest. So, the teams chased small improvement projects for specific customers dreaming of a huge impact across a market without any real possibility of achieving the dream.

One of the punch lines here is that without tangible visibility to the upside, few project teams actually put any energy or attention into the factors that drive the upside. They were leaving these critical drivers of success completely up to chance. When the upside multiples are several times the base value, it is a very good trade across the portfolio to focus on creating the upside, even if you must let a few otherwise good projects go.

For example, suppose you have a portfolio with one ordinary project plus another project with similar returns but that has potential (with some additional resources) for 5 times upside. If you pursue them both you get 2 projects worth of return. However, if you redeploy the resources from the ordinary project to drive the upside of the other project, you net out 4 times ahead.

Many of DuPont’s projects had hidden upside. By identifying this upside and putting energy into creating it, DuPont was able to significantly improve its overall portfolio returns. By differentially managing those projects with significant upside, rather than simply driving execution, they created space for these projects to realize it.

To test the hidden upside issue, participants in the workshops considered factors that could drive the upside in their sample projects. Reasons were varied and tended to be very project specific, but included topics like overdelivering on cost or performance, expanding channel, and finding mainstream (vs. niche) opportunities. Then we asked the participants to be optimistic and estimate, if a few of these factors worked out in their favor, how big would the upside be, expressed as a multiple of the base business case.

The average upside across our group of diverse companies was 3.5 times. This is a bit misleading, as fully 20% of the participants had upsides above 4 times and about 10% above 8 times. A few massive upsides across a portfolio make a huge difference – the returns are non-linear. How many projects with this potential might be in your portfolio? If you can find even a few, it will create dramatic improvements in your return on innovation.

50% of the participants had upsides between 2 and 4 times. This potential is still extraordinary. Many of these projects masquerade as pedestrian projects, they seem just fine the way they are, so why bother pushing the upside? Because there are many of them and it really adds up across the portfolio. Systematically finding these possibilities and helping teams steer towards them can again be massive.

Collectively, 70% of the participants had upsides greater than 2 times the project base value. I would call type of uncertainty this “innovation error” [see sidebar]. The problem here is the failure of visibility and of imagination to find and create the upside. Even if only a few projects make modest improvements towards the upside, the combined effect across the portfolio is huge.

Yet most business processes are designed to eliminate uncertainty or disregard it, under the basic assumption that the uncertainty is “estimation error.” If your project faces estimation error [see sidebar], the risk is a failure to execute, so get on with delivery. Most companies have business processes focused on delivery. Yet among our participants, only 30% had upsides less than 2 times the base where this approach would be appropriate.

Where are you overlooking the upside of your projects? What would the impact be of getting visibility to it and pursuing it?

ESTIMATION ERROR = when the uncertainty in your assumptions is small, creating an upside no more than 2x the base. Business processes for these projects should drive to delivering the base, not getting distracted by the uncertainty. The risk is a failure of execution, so don’t get distracted. Work the execution plans, where possible mitigating the downside and supporting the upside.

INNOVATION ERROR = when the uncertainty in your assumptions creates an upside much larger than your base. Business processes for these types of projects should drive towards learning if the upside is possible – this is more important than merely delivering on a mediocre aspiration. The risk is a failure of imagination, not of execution. Focus on learning plans that demonstrate if the unreasonable upside is possible (or not). Create options for the company to invest more as the upside proves out.

Wounded Projects

As indicated above, DuPont found it wasn’t putting energy into driving the upside of its projects. But it was worse than that. DuPont was inadvertently and systematically wounding its projects, not giving many of them enough resources to have a reasonable chance of success.

On the surface, it seems like the right thing to do. Many project leaders pad project budgets a little, so putting a little resource pressure focuses their minds and drives project leaders to focus and make good use of their efforts. A bit of pressure can drive efficiency, and this is a good thing.

However, it can easily get out of control. Project management systems are designed to get high throughput out of a set of resources, and relentlessly pressure projects. This effect is compounded by the occasionally bad quarter, where project leaders are asked to give a little budget back so the company can support meeting its overall spending targets. Resource management systems tend to allocate scarce resources across the projects, making sure each important project gets some. People, particularly the “A players” are spread thin.

Individually, each of these impacts is small, or might even be beneficial. However, accumulated over the years, it becomes death by a thousand cuts. Project leaders start to ask for what they think they can get, rather than what they need, setting up another unintended dynamic that increases chances of failure. The portfolio is cluttered with many projects demanding attention, and each project gets some, so all important projects make some progress. Yet none has what it needs to win, and decision making is dominated by advocacy and conflict.

Collectively, the impact of these effects is devastating. DuPont found that most of its projects were wounded, with significantly less resources than they needed for even a basic chance at timely success. Further, innovative projects, which tend to have an imaginative element as they try to create something new, were systematically penalized, doing worse that more traditional projects that required less imagination to understand.

To explore this issue in our workshop, we asked our executive participants, “Do your sample projects have the level of labor (FTEs) and funding needed?” Only 13% of participants had sample projects that had 75% or more of the required resources. In this range, we might reasonably interpret this as a kind of positive pressure, driving efficiency.

However, 30% were in the danger zone of supporting projects in the 50-75% level. This isn’t positive pressure for efficiency; it is starvation. But even worse, fully 56% of the sample projects had less than half of the basic level of resources needed for success. This is neglect. Better to kill these projects outright than to have them live on draining resources from the portfolio and draining hope from the staff.

Focus = Resources plus Attention

It turns out that resources are only half the story. Focus to drive innovation is more than just resources, it is also attention. Most innovative project challenge the status quo somehow. They often require new capabilities, new channels, or new business models. They need special creative thinking and energy. They require breaking rules and making exceptions at the right moments.

The people who have the level of power, creativity and judgement to contribute this kind of attention are rare in an organization. They are rarely part of project teams explicitly, perhaps being special technical or marketing resources, or high-level executives (sometimes even the CEO!). So, making innovation successful requires considering how busy these people are. Do they have the attention to drop in from time to time and make that critical contribution that makes the difference between an amazing opportunity and a project that dies on the vine?

DuPont had found that it suffered clutter. These rare and powerful people were reviewing all projects more or less equally. They didn’t really know where to direct their scarce attention. To be sure, there were “strategic” and “priority” projects, but were these really the ones with upside? Many had a tactical urgency, but wouldn’t really drive growth. DuPont rigorously evaluated and then found the short list of projects and upside potentials where this kind of attention might really make a difference and drive meaningful growth for the company. They made tremendous progress by getting these rare and powerful people systematically focused on the right challenges across the portfolio.

Participants in our group considered the level of challenge in their sample innovative projects. How much did a project deviate from the status quo, need special creativity, or otherwise require the attention of the rare and powerful people in the organization. Then, relative to the level of innovation challenge, each participant assessed the level of attention their sample project was actually getting, with 100% meaning it was getting an appropriate level relative to the intrinsic challenge, 50% meaning half the attention, and so on.

The bad news is that only 17% of the sample projects were getting even close to the attention needed, at 75% or more of the requirement. This means that 83% of the projects weren’t getting anything like the attention they needed to make a real success. A terrifying 26% of participants rated their projects as getting less than 25% of the attention required. The participants, like DuPont, were unintentionally condemning some of their best projects to mediocrity because of too much clutter.

Are your most challenging innovation projects actually getting the rare and creative attention they need to break the rules or make large moves that would be impossible inside a traditional phase gate?

We asked our executive participants to combine the resource and attention estimates for their sample projects into a focus factor. They found that on average, their sample projects were only getting 23% of the focus they needed to have a reasonable chance of delivering a timely result. This astounding finding may reflect a bias in the selection of sample projects, that is participants may have picked difficult project. But if true for some part of your portfolio, it would have a massive impact. This figure represents a kind of unintended but nearly criminal neglect in the portfolio.

The Path to Improvement

Each of these effects taken individually, hidden upside and lack of focus (both resources and attention) is bad enough. Taken together, the combined effect is much larger than DuPont and most participants realized. And across a portfolio the systematic effects are devastating. So, the path to an 8 times improvement on your innovation investment, like our participants found, or a 2-3 times improvement across the portfolio like demonstrated at DuPont, has to address the underlying death by a thousand cuts that projects face.

First, rigorously assess the value of your portfolio. Really consider the upside as well as the base case of the project. Determine what level of resources projects actually need (not what they are asking for), based on the innovation challenges they actually face. (If you aren’t yet ready for rigor, consider the simplified assessment tool used by our participants as a first step).

Then make some decisions to declutter. Get rid of the small project that, however good, won’t move the needle on growth. Focus the attention of the rare and the powerful on the few projects with breakthrough upside and significant innovation challenges.

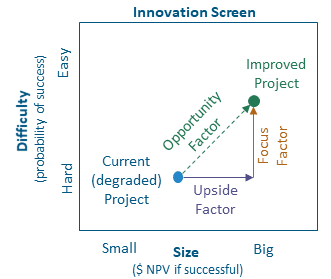

The result will surprise you. The path to improving your returns on innovation is twofold, as shown in the above graphic. First, by focusing (through both resources and attention), you will find that your probability of success of projects increases. Second, by putting energy into the upside of opportunities, the value if successful increases. Together, these create a powerful path to breakthrough growth.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the volunteers that helped facilitate the workshop:

Rupinder Bhathal, Corporate Development, Kyocera

Ravi Chandra, Global Innovation Manager, Rockline Industries

John Patrin, Innovation & Growth Director, DuPont

Bart Schubert, Chief Strategy Officer, CRB

Thanks also to all the companies that participated and assessed sample projects:

| 3Pillar Global | Geisinger | Production Creation Studio |

| Becton Dickenson | Gleason Works | Rheem Manufacturing |

| Brillio | Halyard Health | Rockline Industries |

| Burr Oak Tool | Honda | RXBAR |

| CRB | Kyocera | Schneider Electric |

| DuPont | Lubrizol | Siemens Healthineers |

| Frost & Sullivan | MBX Systems | Ultimate Software |

| GOJO Industries | Nerdery | Ultradent Products, Inc. |

| Novolex | Workfront | |

| Gorilla Glue | Philips |