Making uncertainty your friend in forecasting and goal setting

By David Matheson  11 min read

11 min read

The panic sets in. Who can we blame? What excuses can we offer? How do we manage the surprise?

It seems we aren’t going to hit our numbers.

Next year we resolve to do better. We put more work into predicting the right number. We get more data. We get firmer commitments. We ratchet up our effort, believing that trying harder will improve our forecasting enough to prevent surprises. But it doesn’t work.

In an era of unprecedented access to data and communications, we still miss our forecasts.

Many think “conservative” forecasts are better, but in many cases conservative forecasts are as bad as overpromising.

In discussions with companies as diverse as pharmaceuticals company Alnylam on what to present to the board, to chip manufacturer Intel on improving reliability in setting expectations, to materials company Rogers Corp. on accounting for innovation in long-range planning, we’ve come to a radical diagnosis of the problem.

The underlying issue is that the very idea of an accurate point forecast is fatally flawed. The idea that if we roll up commitments from various projects or departments, will get an accurate commitment is fatally flawed.

A financial roll-up is often a cover-up, hiding the uncertainty. This traditional approach unintentionally creates the surprise and limits management ability to drive upside. The cure is to put uncertainty at the beginning of your forecast process rather than experiencing it as a disappointing surprise at the end, as shown in Figure 1. This improvement turns uncertainty into your friend and increases the chance of hitting upside aspirations.

The traditional approach to making a forecast is to establish a business case from each of several projects, then roll these up to produce an integrated portfolio forecast, as shown below in Figure 2.

If all the projects succeed and deliver as planned, this does reflect a scenario for the portfolio. For example, 2023 total revenue from the portfolio is $139,365 million.

But what is the chance all projects are successful and hit their promise? It just is not likely to occur and so the roll-up sets up for disappointment.

Many companies recognize this and adjust each business case for risk, the chance that projects will not work out. Usually this is done with a risk factor, often applied across the whole portfolio.

For example, an analyst might realize that the organization often delivers about half of the promise, and so she simply multiplies the entire financial roll-up by this risk factor of ½ and uses that as the “forecast”. This would result in a forecast of $69,818 million for 2023 total revenue. A more sophisticated version of risk adjustment puts a risk factor on each project, resulting in a more detailed risk-adjusted forecast. Either way, the most important projects in our example are Everest, Rocky, and K2 plus maybe Rainier as a base hit, as shown in Figure 3 for 2023 revenue.

While we fear failure—not delivering to the promise—the upside is another important source of surprise in the forecast. Many think “conservative” forecasts are better, but in many cases conservative forecasts are as bad as overpromising.

Consider the case of a major agricultural company (who will remain nameless to protect the guilty) that found tremendous demand for a new product. This success should have been the cause of celebration, the culmination of many years of hard work! But manufacturing had based its plant sizes on the carefully negotiated conservative forecast and was caught short. The conservative forecast led to the business case for capital investment at a moderate level of production. It all sounds very reasonable and prudent.

But then when customers loved their product and they needed high levels of production, they could not meet demand. They had no contingency plans because there the upside scenarios were not communicated. Blame and recrimination started. Expensive emergency plans were created and implemented to close the manufacturing gap. It took a few years for manufacturing to catch up and happily the new product became a backbone of the company’s revenue. But they lost a few years of revenue, overspent on capital due to the emergency spending, and few careers ended early—all because they had not considered the upside in their forecasts.

This sort of outcome is bad enough. But the radical diagnosis of the limits of traditional forecasting point to a deeper flaw. The problem is that conservative forecasts actually reduce the chance of hitting the upside. Visibility to the upside scenarios shows which projects matter most and gives an organization a better focus on steering towards better results.

One tech company I worked with made a conservative promise based on delivering on a major customer request for material. They were excited that this important customer might offer them a 5% premium on their standard pricing, and they charged ahead qualifying the material for the customer. But a little discussion showed that the customer was replacing an inferior material that cost far more than the tech company’s replacement. In other words, the tech company had not considered the obvious scenario that they could get a 2 or 3x premium not just a 5% premium. This difference between a 5% premium and a 2x or 3x premium was more important than many entire projects in their portfolio! They did not realize that focusing on the business relationship and pricing was one of the most important opportunities in the entire portfolio and so failed to drive the upside.

In summary, the traditional roll-up method is a cover-up of uncertainty in two ways. Not only does it create the potential for disappointment if you fall short; it reduces the ability to drive upside.

To create more reliable forecasts, reduce the downside risk, and increase the ability to drive the upside, we need to abandon the idea of a point forecast and start with uncertainty. Once we understand the project and integrated portfolio uncertainty, then we can select goals and make forecasts with greater reliability and impact.

Making uncertainty your friend in forecasting will give you not only more reliable forecasts, it will enable you to hit them more reliably.

Uncertainty starts at the project level. It typically comes in two flavors: Difficulty and Size. In other words, how likely are we to succeed, and the range of commercial outcomes? In the tech company example above, Difficulty translates into the ability to qualify the material for the customer, and Size translates into pricing—do we get 5% or 3x premium pricing? Each opportunity typically has specific factors driving Difficulty and Size and understanding these factors is central to project-level uncertainty. But measuring these probabilities and ranges is beyond the scope of this article, so let’s suppose we have some reasonable metrics of uncertainty in these areas.

The core issue for portfolio forecasting is: what does project-level uncertainty mean for portfolio performance? By simulating project-level uncertainty across the entire portfolio, you can get a sense of portfolio performance. In Figure 2, does project Everest hit its $41M goal in 2023? Or maybe it fails and contributes nothing. Or perhaps it falls short at $15M; or maybe is wildly successful and delivers $60M. And what about project Rocky? Or Rainier? All the different combinations of project performance aggregate into many scenarios for portfolio performance and probabilities of achieving them.

The tool for visualizing all these scenarios at once is called a Cumulative Distribution, but let’s just focus on the range of likely portfolio outcomes, as shown in Figure 4, a sort of confidence interval on the performance. For our example in Figure 4, the Upside of 2023 revenue is $90M, but sadly it only has a 10% chance of occurring. At this level of performance, the big projects are doing very well. The Downside of 2023 Revenue is $4M and it can be exceeded 90% of the time. At this level of performance, many projects are failing outright, but some smallish and reliable projects deliver. A Median level of performance, with a 50-50% chance of hitting it is $40M—so the balance of probability is in the middle of the range.

![2021_June ValuePoint - Figure 1, 4 [photoutils.com] ValuePoint Figure 4: Comparison of Range of Portfolio Performance Scenarios to Traditional Method](https://smartorg.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/2021_June-ValuePoint-Figure-1-4-photoutils.com_-1024x206.jpeg)

For any target level of portfolio performance, there is a probability that the organization will meet or exceed it. The Downside, Median and Upside performance levels give a standard sense of the range.

This uncertain assessment of portfolio performance shows why traditional forecasting often leads to surprise. If you forecast based on the simple roll-up in Figure 4, at $139M, there is less than a 10% chance of hitting that figure since it is above the Upside scenario for portfolio performance. The detailed analysis shows it has less than a 1% chance of being achieved! But we didn’t really believe the naïve roll-up anyway, so let’s consider the risk-adjusted one of about $70M. It is still optimistic, above the Median of $40M but below the Upside of $90M, and in the detailed analysis risk-adjusted forecast has only a 40% chance of achieving it.

It isn’t just naïve or risk-adjusted roll-ups that are problematic. It is ANY specific forecast. Make a forecast on the lower end, say $20M for 2023 revenue, between the Downside and Median of portfolio performance. This has a 67% chance of hitting it, but a 33% chance of exceeding it. No amount of precision or working the assumptions on a specific forecast portfolio is going to increase its reliability. Working harder on forecasting to chase illusory precision or accuracy is a waste of time.

It depends on the purpose of the forecast and your portfolio strategy. Usually, organizations want to set a goal and expectation that they can hit most of the time. The Downside forecast of $4M gives you a 90% chance of hitting it. Or if you wanted a bigger goal, you might be a little more aggressive, selecting perhaps $20M (which a more detailed analysis would put at an 80% chance of success).

But suppose your business objective is “go big or go home”. Here you would focus on the Upside, of $90M and accept that this is a risky strategy with only a 10% chance of success. Venture Capital firms work this way.

Or if you are the manufacturing organization that has to support the portfolio performance, as in our agricultural example, the best forecast might be the entire range. Be sure you can produce at the capacity to deliver on the $4M scenario. But have contingencies in place to quickly ramp up if we get to the $40M Median or $90M Upside scenarios. Fewer careers would have been cut short if the manufacturing organization of the agricultural organization had had these sorts of contingency plans and hadn’t been caught short by upside in project success.

Or perhaps you are the innovation organization. You would like to increase the chance of hitting the Upside goal. Can you deliver breakthroughs to lower the difficulty of key projects or increase their upside potential? Success on these efforts will make these Upside targets more likely in the future.

But which projects matter most?

A traditional roll-up gives only limited insight into which projects matter to reach which goals. The uncertain portfolio forecast provides much greater insight into what teams and management need to focus on to hit each forecast: reliable delivery or upside. In other words, you can use the understanding of uncertainty to improve your chances of hitting both the Downside and Upside levels of performance!

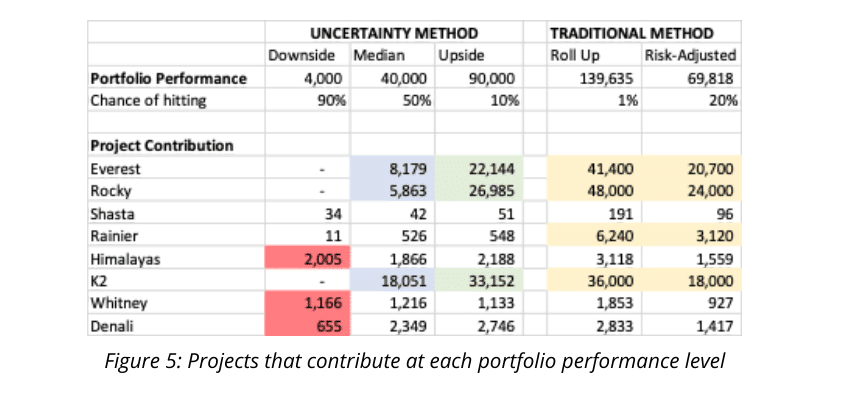

Let’s start with a reliable forecast. Figure 5 expands the Portfolio Performance Comparison to show which specific projects are contributing to each Portfolio scenario. For the Downside forecast, the projects that matter are the Himalayas, Whitney, and Denali, shown in red. The others do not contribute, in fact, they can fail and you can still hit the goal. So if you are only concerned with hitting a minimum level of performance, cancel all the other projects.

But of course, you’d like to do much better than the Downside if possible. So let’s take the perspective of the innovation organization. Their job is to improve the chances of hitting the Upside target of $90M, which at present has only a 10% chance of occurring. They should focus on the projects that matter most in that scenario, reducing their difficulty or increasing their upside. Figure 5 shows that in the Upside forecast, K2, Rocky, and Everest are the big hitters, shown in Green. The other projects don’t really contribute. The innovation organization should focus on those.

In the example of the tech company qualifying its material, the 5% premium was like project K2 in the Downside scenario. It wasn’t really that exciting from the perspective of contributing to the base goal. But its Upside was tremendous! One of the most important opportunities in the entire portfolio was putting better business development people on the project and seeing if they could negotiate value pricing. Depending on how well the negotiation went, the project could have been a wash, like K2 in the Downside scenario or it contributes over 1/3 of the entire revenue target for the entire company, like K2 in the Upside scenario.

One startling implication is that if the innovation organization does make progress on these three projects and the Upside scenario starts to look more likely, you should consider canceling the projects needed for the Downside scenario. If you learn that K2 is heading to its upside, do you really want to continue with a sure thing but small Whitney? These Downside projects don’t contribute to the Upside scenario and may become a distraction for the organization. By changing direction and focusing, you build on the momentum the innovation organization has created and further increase your chances of hitting the upside.

This Portfolio Pivot is only foreseeable if you have a sense of what is driving the Upside of portfolio performance! It simply isn’t visible in a traditional roll-up view.

Finally, notice that projects Denali and Rainier don’t contribute significantly to any scenario for aggregate performance. So consider dropping them completely. Compare this insight to the traditional approach, in which Rainier seems like an important project, even though it is unnecessary.

A no-surprise forecast starts with the range of portfolio performance. In our example, between $4M and $90M is a range you can be fairly confident in. While that may be too wide for simple communication, it is more accurate than any single-scenario forecast. Starting the range improves understanding.

The specific forecast you make depends on what you want to accomplish with the forecast. Reliable forecasts at the low end of the range that have high chances of success are different than stretch goals at the high end of the range. Selecting the appropriate forecast(s) for goal setting improves expectations and alignment.

The range forecast improves focus in project selection. Since each scenario for portfolio performance relies on different projects, you can set project-level goals appropriately. Projects contributing to a Downside forecast can be managed as reliable base hits. Projects contributing to an Upside forecast are managed for de-risking and driving upside.

Finally, you will have insight into a better strategy for delivery. You will know when to pivot, dramatically shifting resources to go after an opportunity that has proven itself out.

Making uncertainty your friend in forecasting will give you not only more reliable forecasts, but it will also enable you to hit them more reliably. In particular, it will increase your chances of driving the Upside. Don’t let traditional forecasting cover up uncertainty and blind you to the opportunity in your portfolio.

Learn more about how Portfolio Navigator’s new version 8.3 gives you the capabilities to understand aggregate performance, improve your forecasting, and increase your ability to drive the upside.