Sufficiency and Significance

By David Matheson  4 min read

4 min read

An earlier ValuePoint introduced the Four Critical Questions for Decision-making in Strategic Portfolio Management (see sidebar). In this edition, we’ll look at two questions about Sufficiency and Significance.

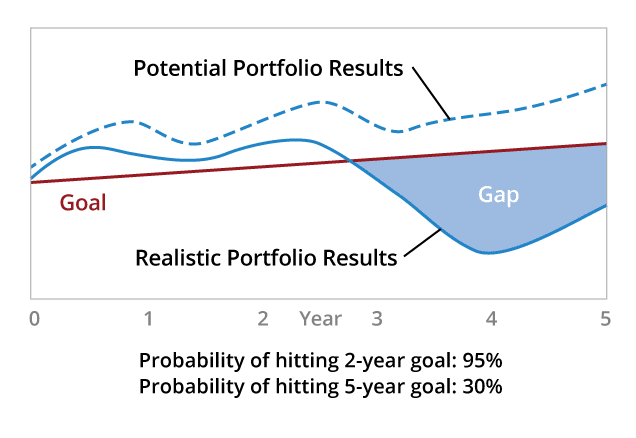

The Sufficiency question asks, “Do we have enough to achieve our goals?” In particular, is there enough potential in the portfolio of innovations, new products and process improvements to give the organization a good chance to hit its growth targets? Simple roll-ups rarely address this issue because project uncertainty often makes portfolio forecasts seem unreliable, which creates executive discomfort about having enough.

Most portfolio evaluation tools don’t provide clarity and confidence about the portfolio’s value and range of financial performance over time. Addressing Sufficiency requires clearly understanding the uncertain performance of the portfolio over time relative to goals. A good portfolio process shines a (sometimes painful) spotlight on the gaps between uncertain performance and goals over time, which motivates and enables real choice.

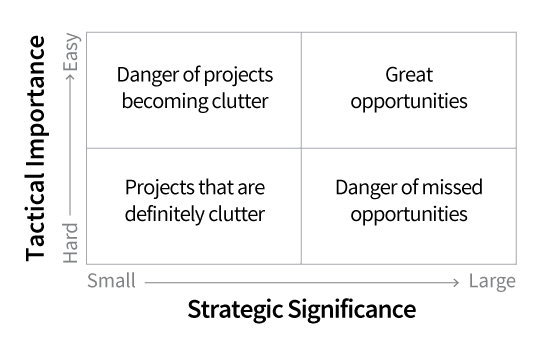

Most portfolios are cluttered with uninspiring and mediocre projects, each of which serves a perceived tactical need. Often projects are given priority based on “strategic” handwaving that clouds the issue. Sometimes internal champions exploit company politics to ensure their projects keep their funding and stay on the development schedule. But these methods of assigning importance often ignore the significance of the project.

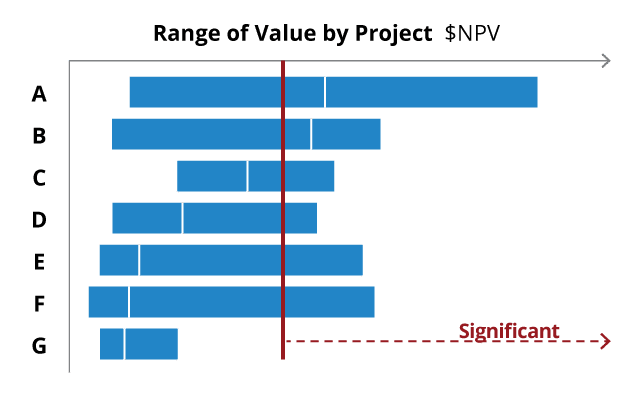

Figure 2. Significant projects have high expected value and/or high upside potential.

While clutter projects often seem inexpensive taken individually, this misses their opportunity cost: time and attention spent on small projects distracts from significant projects. These insignificant projects won’t move the needle for our goals or inspire our people to do something great. However, they will take actual management attention and other resources away from to other projects that could create real upside for our company. All insignificant, unimportant projects are just clutter. And many tactically important projects are also clutter, but we just don’t realize it because we don’t see their low significance.

Removing clutter from a portfolio allows us to focus on the projects that matter, ones that will make substantive contributions to achieving our goals. That includes not just managing to realize the expected value of the project as it stands today, but looking for ways to drive the value of the project to the upside that we believe is achievable.